instruction: alignment is everything

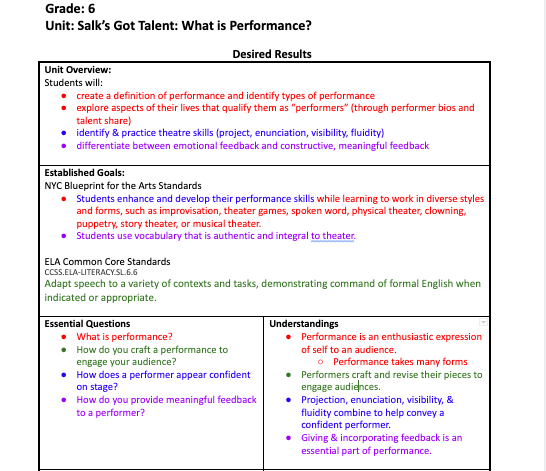

In one of my first years teaching, we spent a staff meeting giving peer feedback on unit plans through the lens of assessment--specifically as it related to the Common Core, which was newly rolled out. A colleague, for whom I had great respect, looked over my ambitious list of learning standards, based on a combination of New York City Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in the Arts benchmarks and Common Core Speaking and Listening goals, and he laughed. He scrolled through my lessons and said, “But you’re not assessing any of that. What do you actually want them to learn?”

“What do you actually want them to learn?”

This question has stuck with me through all manner of initiatives and reforms. We let so much educational jargon and minutiae cloud our path to what we want our students to learn. A single lesson might address a myriad of arts standards, and it might even reinforce a variety of Common Core Literacy or Speaking & Listening standards. But what do you really want your students to learn? That is what you are assessing. Those are the standards you want to focus on. Those are the standards to which you want to align everything else you do in your classroom. And it doesn’t need to be a very long list.

A couple of years ago, our school embarked on a partnership with Heidi Hayes Jacobs. Known for her work in 21st century technology, we were harnessing her expertise in unit planning. My biggest epiphany from that PD initiative was alignment. We drew up our unit plans and assigned each standard a color. Then we were told to color-code every skill, concept, assessment, activity, and reflection question in our plans as it aligned with the standard. Yes, I realize how tedious this sounds, but holy cow! What an eye-opening exercise! Imagine how many activities you build into your curriculum that have nothing at all to do with what you actually want your students to learn. I promise it’s way more than you think. I discovered entire lessons that belonged in different units altogether. I learned that there were so many more useful skills I could be developing. I found assessments that were flat-out irrelevant. I wasn’t doing things all wrong, but I was able to pinpoint exactly what I could be doing better. And it helped my students do better, too.

When you focus on what you want students to learn, you become better able to determine if they did. You can start by identifying students’ strengths and challenges in your class. To implement a phrase from the Universal Design for Learning framework, what are their barriers to learning? Then you can begin to offer tools to support them. When you know what you want them to learn, you can start to reimagine how they can demonstrate that knowledge.

Perhaps your goal is for your theatre students, for example, to demonstrate an understanding of character intention in a monologue performance unit, but they are facing one of the following barriers:

They have crippling stage fright.

They are absent/pulled out for services too frequently to have ample rehearsal time.

They have a speech impairment that prevents them from meeting performance expectations.

Some combination of these things...

Something entirely different...

You can begin to imagine alternate ways someone might show that they understand character intention. They can:

Assess their own work and provide evidence to support their observations.

Assess other students’ performances and do the same.

Direct another student.

Draw their character’s intention in a comic strip.

Film their monologue performance at home.

Complete a worksheet about character intention.

Write a follow-up monologue.

Do some combination of these things...

Do something entirely different...

Your instinct here is to ask if this is fair to the students who are getting in front of the class and performing, and this is where it’s important to know your students. Maybe this would spark a revolt, and so you have to give everyone the option of how they want to demonstrate understanding. After all, if your goal is character intention, then why can’t it be shown in any of the ways above? Why must it be performed as a monologue in front of an audience? In doing this type of thinking, you might discover that your goal is actually “demonstrating character intention through performance.” And that’s okay! Now, start there. Rinse and repeat.

Good teaching is knowing what you want to teach and knowing how to help your students learn it. When you can identify what you actually want them to learn, everything else will fall into place.

This stuff is hard. It’s good teaching. And good teaching is hard. You’re not going to hit all these things every day. Or every unit. Or even every year. (And that is why the Danielson Framework was developed to help provide teachers with next steps for their pedagogy.) Even the most skeptical of teachers have told me that this framework has changed the way they ask questions of their students. We so often make the mistake of assuming that kids “get it.” And this is a nice reminder that maybe they don’t.

We fall into patterns as teachers. We have our rhythm, we have our energy, we have our bag of tricks. Sometimes it’s helpful just to be reminded of what the possibilities are and ways break you and your students out of the “turn-and-talk, share out” rut. When you try a new way for students to share their thinking, you give space for students to contribute in different ways. Remember that we weren’t all the kids who raised our hands to share, but that doesn’t mean those kids are the only ones engaged. Varying your discussion format allows kids to break from their typical classroom roles: the hand raiser, the silent observer, the active listener, the side-commenter. It’s just another way that, as teachers we are responsible for knowing who’s in the room and teaching them the way they need to be taught.